Now that you have all your equipment and some idea of what to do once you hit the trail, you are ready to plan a trip. The planning breaks down into who, what, when, where and how.

Who

Since the choice of companions is so important, start with that. To begin, don’t go alone. Solo wilderness hiking is only for very experienced backpackers, and even for them I don’t encourage it. If you want to take your family on a backpacking trip but are unsure how well you yourself will make out, go with some other people first to gain confidence. Or perhaps you will go with your spouse to get a little experience before taking your children. If you have no family, and you won’t feel embarrassed about your lack of experience—which you shouldn’t—ask an organized backpacking group in your area whether they have a trip you can go on. Sierra Club sections are the most obvious among many such groups. Generally, the people on a group trip will be at least adequate companions, because most of them will have had some experience.

Under “Who” comes the question of taking pets. Dogs are allowed anywhere in national forests but are discouraged in wilderness areas and forbidden on trails in national parks. I oppose taking a dog, but if you must take a dog along, remember that it may get cold at night if not in a tent, and try to crawl in bed with you. Remember also that rocky trails can hurt its feet and bears could kill it. Dogs are only visitors to the wilderness too. Keep your dog under strict control to prevent it from disturbing or harming wildlife. “Doggie packs,” in which the dog can carry at least its own food, are available at some backpacking-supply stores.

Fig 6-1 A backpacking dog

What

If you are deciding what type of trip to take, keep it simple. Don’t let yourself in for 200 miles of driving each way on a week end. Plan on only a few trail miles per day—somewhere between 2 and 5 depending on the terrain. Limit the number of people to four or so. Even two is not too few. Choose a trip that is entirely on good trails. Allow plenty of time for each phase of the trip. Plan the simplest menu you can stomach. And as I said, don’t depend on fish or wild plants for any part of your food.

Finally, don’t plan a trip you won’t be in shape for. Let’s put it another way: get in shape to do the trip you’d like to do. That may require regular conditioning exercise for months in advance (see Section 8).

When

The answer to when depends on two things: whether you crave solitude, and when you will have time. If you don’t want to see a lot of people on the trail, go between Monday and Friday, go before the Fourth of July or go after Labor Day—if your schedule will allow it. Many beginners who depend on the presence of others for a feeling of safety and security prefer to see a number of other people.

Whenever you go, you should allow at least two nights away from home. Getting up, leaving home, driving to the trailhead, walking to your campsite, making camp and cooking dinner all in one day is too taxing. For some people, the 3-day weekend every week is already here, and for the rest, it is on the way. Meanwhile, try to get away early enough Friday night to drive to the trailhead in time to get plenty of sleep. More adventurous backpackers may walk into the wilderness in the dark after eating dinner at the trailhead. If the moon is half full or more, they’ll have plenty of light.

For me, when is September and October, because the High Sierra, where I go, is so unspeakably beautiful then and because the crowds are gone—except near trailheads on the opening week end of deer season, which I avoid. In other Western mountains, where the fall rains—and the first snows—come earlier, October is rather late. I also like to go early in the season, sometime around late June, just after the ice has broken up on all but the highest lakes. The mountains then give off a marvelous feeling of awakening from winter—and the mosquitoes haven’t yet hatched. Around the country generally, summer is the best time, but in the Southern states and in desert areas, summer is really too hot. More and more backpackers are breaking the summer mold and choosing the best time in their particular bailiwick.

Sometimes the weather has a way of saying no to the best of plans. If official forecasts for the area you were planning to go to strongly predict a storm, you should either postpone the trip or drive up prepared to turn around if the forecast seems to have been correct.

Where

Despite the population explosion and the backpacking explosion, there are still plenty of places to go, and there will be for years to come. (Whether there will always be plenty of places to go is not nearly so clear. If it’s important to you that the wilder ness be preserved, get active in the fight to preserve it. Someone is always trying to carve off a hunk of it for mining, lumbering, resort building, or some other pecuniary purpose.)

You may decide to choose a trip from a guidebook. Wilder ness Press guidebooks are the best there are. Or perhaps you will learn about a good trip from a friend.

Whatever itinerary you decide on, be sure everyone who is going understands the plan and agrees to it.

In planning where to camp each night, remember you can camp legally almost anywhere in a national forest, and you can camp happily anywhere that has the campsite attributes you desire. You can even camp where there is no water, if you carry enough.

How

How will you make the trip? In particular, what will you need, and how will you transport it to your destination in the wilder ness? Some of what you need is in the closet where you keep your equipment. Some of it is on the shelves of supermarkets and the shelves of backpacking-supply stores.

Having decided who, what, when and where, you know pretty well how much equipment, food and supplies you will need, and you know how many people of what size and what strength are available to carry it all. So now it is time to make lists. Have each person make a list of all the equipment, clothing and supplies he needs for himself. (The list in Section II will get you started.) If you will be the trip leader, make a list of what the group will need, and check over the personal lists of the other people. All this is best done several days in advance, to allow time for having second thoughts and remembering things temporarily forgotten.

Prepare a menu for all meals, and after everyone agrees to it, make a list of all the food required for that menu. Buy it and prepackage it (see Section 4). Keep perishables in the refrigerator as long as possible. The night before you leave, ass in one place all the packs and everything that is to go in them. (If you do this the day you leave, you are likely to do it so fast that you make mistakes.)

Divide things up so that each person carries their share. People often ask me, “How many pounds should I carry?” There is no flat answer—it depends on your size, your strength, your physical condition and the distance to be traveled. A strong person in good condition weighing 200 pounds can comfortably carry 50 pounds (25 percent of his body weight) for many trail miles. Most of us should not carry more than 20 percent of our body weight if we want to have a pleasant trip. If you are carrying extra fat on your body, you can carry even less weight in your pack.

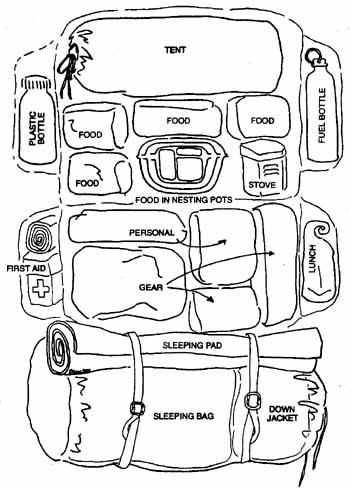

When you put an item into a pack, check it off on the check list. Pack heavy things close to your back and up high, so that they will ride as near as possible to your center of gravity. But make sure nothing hard (like the rim of a pot) is where it will dig into your back. If you have an external-frame pack, tie your sleeping bag, in its stuff sack, onto the packframe below the packbag. An ensolite pad will roll small enough to go under the packbag also; other pads may have to go under the top flap of your packbag.

Fig 6-2 a well-ordered external-frame pack

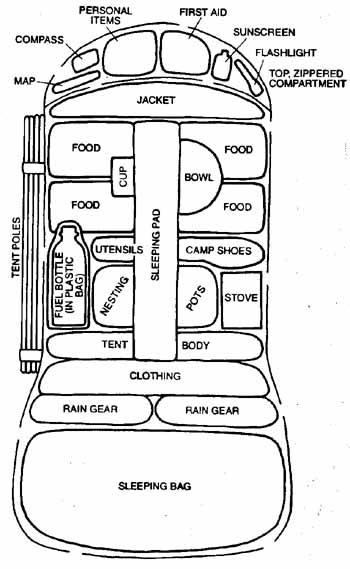

When packing an internal-frame pack, take special care to keep the load balanced and the weight distributed properly. Start packing with all the compression straps loosened. Fill the bottom of the pack—or the sleeping-bag compartment if there is one—with your sleeping bag and clothing. You may want to retain your jacket to pack on top for easy access. Now add the rest of the load, putting the heaviest items where they will ride near your back, behind your shoulder blades. Distribute the weight evenly on each side to avoid being lopsided. I use assorted sizes and colors of stuff sacks to keep my things organized. Your rolled sleeping pad can be attached outside the pack with straps, or, if there’s room, vertically inside the pack. I put my tent poles on the outside of the pack, lashed to one side. Without them, the tent body, fly and stakes are in a more manageable shape to fit in my pack or be apportioned among my companions. The top compartment is for items you want to keep handy: sunglasses, map and compass, sunscreen, etc. Once the pack is full, tighten the compression straps. This will compress the load and prevent it from shifting as you hike.

Fig 6-3 a well-ordered internal-frame pack

A last-minute search of your car will probably turn up anything you forgot to put in your pack. If you are taking a bus or train to the trailhead, or hitchhiking, you had better pack everything at home.

PREV: Day Hikes—A Prelude

NEXT: Trailhead Tips

All Backpacking articles

© CRSociety.net